This one's for Black History Month 2010.

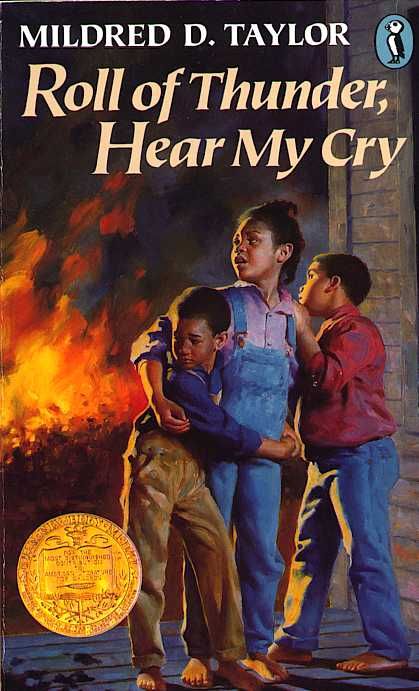

Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry, by Mildred D. Taylor has won several major publishing industry commendations and awards including the Newbery Award for 1977; I'd like to bestow my own reader award for the dozen fast-reading chapters in a book originally intended for middle- or high-school ages but that hardly talks down to a more "mature" audience and, I imagine, most of the vocabulary is basic enough for a bright 4th or 5th grader.

The story happens in post-emancipation Mississippi USA during the Great Depression of the early 1930s. The author doesn't specify an exact locale but refers to a fictional town of Strawberry as well as the real city of Jackson where, by the way, author Mildred Taylor was born and my own grandfather grew up. Spokane County in Washington State was the only one I found with a Google search, so that's one for the book, as well. And this was three decades prior to the Civil Rights movement that with legal decrees only started initiating the dawn of desegregation followed by sometimes grudging, occasionally truly triumphant integration of Black Americans and White Americans. Interestingly, until mid-20th century only Blacks and Whites qualified to become American citizens; most of the country remained racially and ethnically suspiciously divided (and still is), with what feels like endless disputes over the international border between California, Arizona, Texas and Mexico.

First-person narrator Cassie Logan is the young teen daughter of Mary, a school teacher and of David, who spends a lot of time away from home laying railroad track in neighboring Louisiana; grandmother Big Ma, Uncle Hammer and a few other elders provide some backstory and lots of historical perspective. Biblical themes of land, justice and peoplehood run throughout the book, punctuated remembering and recounting tales of Southern Slavery punctuated along the way with reflections about injustice and inequalities and hints of daring hope for a truly free future. Each successive generation is willing to settle for less and more able to trust dreams of a different reality down the road--if not now, when? Mildred Taylor has written so skillfully from Cassie's perspective you'd think she'd actually lived the events, though she tells us her own father was very much like David in the book and as a youth he basically was Cassie's brother Stacey. Christopher-John and Clayton Chester, a.k.a. "Little Man" complete the trio of Cassie's brothers. David spends a lot of time away from home laying railroad track in neighboring Louisiana

The Logan family is privileged to own 400 acres of land; in 1887 Grandpa bought 200 acres that by the year 1933 had no mortgage note to pay yet still had taxes; in 1918 he acquired 200 additional acres that during the time of the book had mortgage plus taxes. The Logans and some of their Africa-American neighbors recognize land as gift that further will provide crops that will enable them to pay taxes and the mortgage on the land that will keep them living there and will continue to yield food for their dinner table.

In some ways scripture views land, the earth, as inalienable gift, Leviticus 25:23 famously says, "The land shall not be sold in perpetuity, for the land is mine. For you are strangers [aliens] and sojourners with me." God is the creator and the original owner but wait, it all belongs to Him, anyway! In Native American culture, too, land cannot be sold. However, access to rich, healthy, well-stewarded ground is essential for our mutual survival, yet during the Jubilee Year, the 50th year, the one of 7 times 7, the land reverts to its original (human) owner/steward. "They" say land is inalienable gift, yet "they" also observe all wars are about territory and we have the concept of real estate, real property.

The Logan family related to the dominant White-controlled economy sometimes with fear-tinged submission, at times with almost play-acting "yes sir, no sir, of course, ma'am" behaviors amidst finding true refuge and safety in a solid, respectful and respecting family of parents, their offspring and the dad's mother, Big Ma. The church that has given its name and a lot of funding to Great Faith elementary school play major roles, too.

Although earlier on in the novel we find examples of death-dealing and destructive fire, closer to the conclusion of the book, fire becomes redemptive as Cassie's father David torches a portion of his own cotton crop in a prescribed burning that directs the Whites in power from possibly pursuing a handing or lynching because they need to prevents the fire from spreading to their own land; for a while the fire brings along with it the visible reality of White and Black "children of slaveholders and children of slaves" working compatibly side-by-side.

And oh, of course there's a prominent White character who is on the side of the Blacks, the lawyer Mr. Wade. And we have the Wallaces, which sounds like a code name.

My experiences growing up around grandparents heavily influenced by Southern social and cultural practices made me think a lot about what I read in Roll of Thunder. I recognized a bit of the attitudes, though tempered by recognition of mutual humanity and mutual needs. The food was familiar, too; what got called Soul Food for a while was exactly the same vittles as poor(er) White Folk typically ate. By the time my grandparents reached New England they'd owned farms and worked the land in Nebraska and North Carolina, and though they'd become urban cliff-dwellers they retained heavy respect for the land. Need I mention we often enjoyed black-eyed peas, grits, cornbread and biscuits? I attended high school in an inner-city school that imagined it at least could desegregate and maybe even integrate some day and did my second undergrad stint at a university originally formed for non-traditional students that included a lot of African-Americans and other distinctive groups. Later on as an adult I lived and served in a predominantly African-American community, where I discovered my familiarity and relative easiness with African-American cuisine and customs coupled with my relative lack of stereotyping and assumptions was a powerful asset to bring to the situation. If I had doubts about my abilities - and who doesn't at times? - my horror at the words and behaviors of some outsiders who came in for volunteer or paid work constantly assured me.

What have you been doing for Black History Month? Just wonderin...

"reads like a real-life experience" — my amazon review

No comments:

Post a Comment

thanks for visiting—peace and hope to all of us!